Calculating Standard Deviation on Streaming Data

Moving Average on Streaming Data (4 Part Series)

This article is a continuation of the one about the moving average, so it’s probably a good idea to read that one first.

In this article we will explore calculating variance and standard deviation incrementally. The idea is to provide a method that:

- Can calculate variance on a stream of data rather than needing all of the data to be available from the start.

- Is “numerically stable,” that is, has fewer problems with precision when using floating point numbers.

The result I present in this article, known as “Welford’s method,” is slightly famous. It was originally devised by B. P. Welford and popularized by Knuth in The Art of Computer Programming (Volume 2, Seminumerical Algorithms, 3rd edn., p. 232.).

The math for the derivation takes a bit longer this time, so for the impatient, I’ve decided to show the JavaScript code first.

The core logic just requires us to add this extra bit of code to our update method:

const dSquaredIncrement =

(newValue - newMean) * (newValue - this._mean)

const newDSquared = this._dSquared + dSquaredIncrement

It’s interesting, right? In the formula for variance, we normally see the summation Σ(valuei - mean)2. Intuitively, here we’re kind of interpolating between the current value of the mean and the previous value instead. I think one could even stumble on to this result just by playing around, without rigorously deriving the formula.

What is

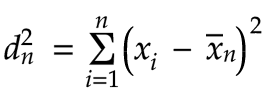

dSquared? It’s a term I made up for the variance * (n-1), or just n, depending on whether we’re talking about sample variance or population variance. We’ll see this term in the mathematical derivation section further down in this article. Also see my article The Geometry of Standard Deviation.

Below is a simple implementation that calculates the mean, the variance, and the standard deviation incrementally as we receive values from a stream of data:

class RunningStatsCalculator {

constructor() {

this.count = 0

this._mean = 0

this._dSquared = 0

}

update(newValue) {

this.count++

const meanDifferential = (newValue - this._mean) / this.count

const newMean = this._mean + meanDifferential

const dSquaredIncrement =

(newValue - newMean) * (newValue - this._mean)

const newDSquared = this._dSquared + dSquaredIncrement

this._mean = newMean

this._dSquared = newDSquared

}

get mean() {

this.validate()

return this._mean

}

get dSquared() {

this.validate()

return this._dSquared

}

get populationVariance() {

return this.dSquared / this.count

}

get populationStdev() {

return Math.sqrt(this.populationVariance)

}

get sampleVariance() {

return this.count > 1 ? this.dSquared / (this.count - 1) : 0

}

get sampleStdev() {

return Math.sqrt(this.sampleVariance)

}

validate() {

if (this.count == 0) {

throw new StatsError('Mean is undefined')

}

}

}

class StatsError extends Error {

constructor(...params) {

super(...params)

if (Error.captureStackTrace) {

Error.captureStackTrace(this, StatsError)

}

}

}

Let’s also write the code for these statistics in the traditional way for comparison:

const sum = values => values.reduce((a,b)=>a+b, 0)

const validate = values => {

if (!values || values.length == 0) {

throw new StatsError('Mean is undefined')

}

}

const simpleMean = values => {

validate(values)

const mean = sum(values)/values.length

return mean

}

const simpleStats = values => {

const mean = simpleMean(values)

const dSquared = sum(values.map(value=>(value-mean)**2))

const populationVariance = dSquared / values.length

const sampleVariance = values.length > 1

? dSquared / (values.length - 1) : 0

const populationStdev = Math.sqrt(populationVariance)

const sampleStdev = Math.sqrt(sampleVariance)

return {

mean,

dSquared,

populationVariance,

sampleVariance,

populationStdev,

sampleStdev

}

}

Now let’s compare the results with a simple demo:

const simple= simpleStats([1,2,3])

console.log('simple mean = ' + simple.mean)

console.log('simple dSquared = ' + simple.dSquared)

console.log('simple pop variance = ' + simple.populationVariance)

console.log('simple pop stdev = ' + simple.populationStdev)

console.log('simple sample variance = ' + simple.sampleVariance)

console.log('simple sample stdev = ' + simple.sampleStdev)

console.log('')

const running = new RunningStatsCalculator()

running.update(1)

running.update(2)

running.update(3)

console.log('running mean = ' + running.mean)

console.log('running dSquared = ' + running.dSquared)

console.log('running pop variance = ' + running.populationVariance)

console.log('running pop stdev = ' + running.populationStdev)

console.log('running sample variance = ' + running.sampleVariance)

console.log('running sample stdev = ' + running.sampleStdev)

Happily, the results are as expected:

C:\dev\runningstats>node StatsDemo.js

simple mean = 2

simple dSquared = 2

simple pop variance = 0.6666666666666666

simple pop stdev = 0.816496580927726

simple sample variance = 1

simple sample stdev = 1

running mean = 2

running dSquared = 2

running pop variance = 0.6666666666666666

running pop stdev = 0.816496580927726

running sample variance = 1

running sample stdev = 1

Okay, now let’s move on to the math. Even though the derivation is longer this time around, the math is not really any harder to understand than for the previous article, so I encourage you to follow it if you’re interested. It’s always nice to know how and why something works!

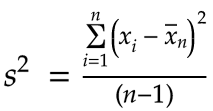

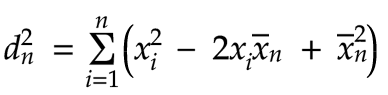

Let’s start with the formula for variance (the square of the standard deviation):

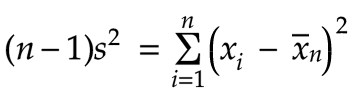

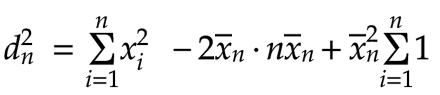

Next we multiply both sides by n-1 (or n in the case of population variance):

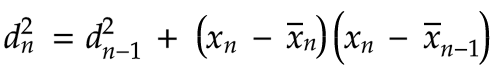

I’ll define this value as d² (see my article on the geometry of standard deviation):

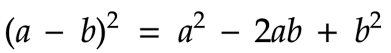

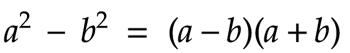

We can expand this using the following identity:

Applying this substitution, we get:

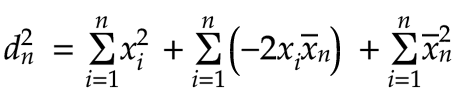

Let’s break up the summation into three separate parts:

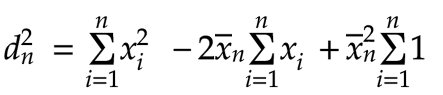

Now we can factor out the constants:

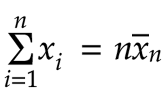

As with the previous article, we’ll use the following identity (total = mean * count):

Substituting this for the summation in the second term of our earlier equation produces:

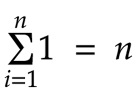

The sum of 1 from i=1 to i=n is just n:

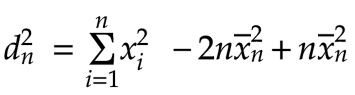

Therefore, we can simplify our equation as follows:

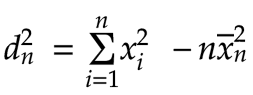

We can combine the last two terms together to get the following:

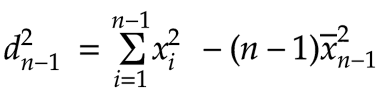

Now that we have this result, we can use the same equation to obtain d² for the first n-1 terms, that is for all the values except the most recent one:

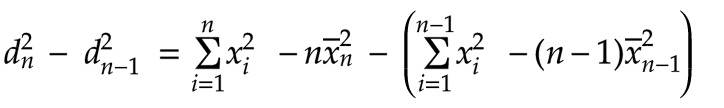

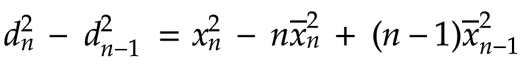

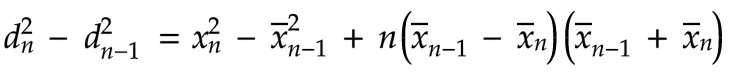

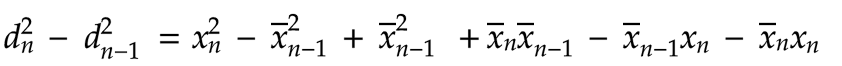

Let’s subtract these two quantities:

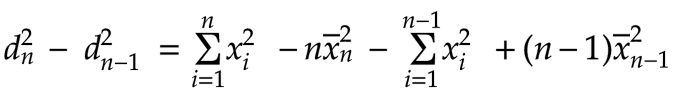

Multiplying the -1 through the expression in parentheses, we get:

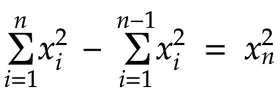

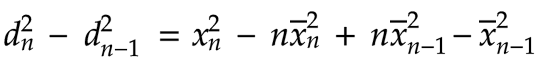

When we subtract ∑x²i up to n - ∑x²i up to n-1, that leaves just the last value, xn2:

This allows us to remove the two summations and simplify our equation:

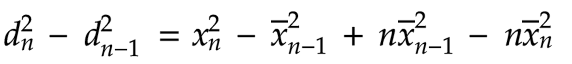

Multiplying out the last term gives:

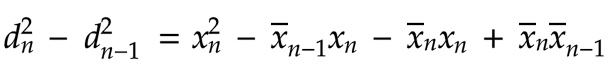

Rearranging the order, we get:

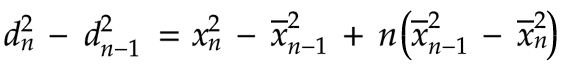

Factoring out the n in the last two terms, we have:

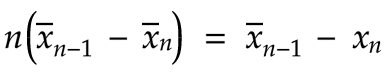

We know that:

Let’s apply this to the expression in parentheses in our equation:

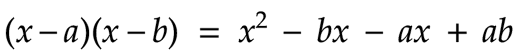

We’re almost there! Now it’s time to apply the following identity, which was derived at the very end of the last article:

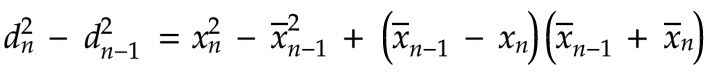

Applying this identity, gives us:

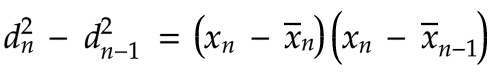

Multiplying through, we have:

We can cancel out the subtraction of identical values and rearrange a bit to obtain the following:

We know that:

This allows us to simplify our equation nicely:

We can now add d2n-1 to both sides to get our final result!

It was a bit of a long trek, but we now have the jewel that we’ve been looking for. As in the previous article, we have a nice recurrence relation. This one allows us to calculate the new d2 by adding an increment to its previous value.

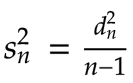

To get the variance we just divide d2 by n or n-1:

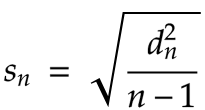

Taking the square root of the variance in turn gives us the standard deviation:

References:

- Incremental calculation of weighted mean and variance, by Tony Finch

- Accurately computing running variance, by John D. Cook

- Comparing three methods of computing standard deviation, by John D. Cook

- Theoretical explanation for numerical results, by John D. Cook

Related: